Breakfast, Crepes, and a Lean Lesson in Visual Management

Earlier today, I had the chance to enjoy breakfast at a small local creperie. The food itself was excellent, but what stayed with me long after the meal wasn’t just the taste. It was the way the team had integrated visual management into their service. Subtle, simple, and effective, it provided a live demonstration of Lean principles applied outside of traditional industrial or healthcare settings.

At first glance, there was nothing flashy. No high-tech systems, no elaborate signage—just thoughtfully arranged ingredients, attentive service, and a process that flowed naturally. Yet every element was intentional, supporting accuracy, efficiency, and alignment. For those of us working in operations or improvement, moments like this are illuminating reminders that Lean is not confined to factories, hospitals, or offices. It exists wherever people design processes that make work easier, safer, and more effective.

Visual Management in Action

One of the key takeaways from my breakfast experience was how visual management was used to prevent errors. In Lean thinking, visual management often refers to displays that expose problems so they can be addressed quickly. What I saw at the creperie was slightly different: the visuals were designed to prevent problems before they happened.

Behind the counter, every ingredient had a dedicated, labeled container, arranged neatly and visibly. From savory ham and cheese to sweet strawberries with Nutella, each item was displayed clearly for the servers. These visual cues acted as a reference, allowing staff to assemble orders accurately without having to ask questions or verify information with the kitchen. The result was consistent, timely service, even during busy periods.

For operators in manufacturing or healthcare, this principle translates directly. Clear visuals can guide staff, reduce cognitive load, and prevent mistakes, whether on a production line, in a surgical suite, or on a patient care floor. The difference lies in using visual management not just to detect issues but to prevent them—proactive rather than reactive.

Clarity Prevents Confusion

A common challenge in any operational environment is reducing errors caused by ambiguity. Visual cues serve as a form of silent communication, clarifying expectations for everyone involved. At the creperie, this meant servers could immediately see what each dish required, reducing reliance on memory or verbal instructions.

In Lean operations, clarity is equally critical. Visual controls, whether a parts board on a shop floor or a medication tray in a hospital, allow staff to focus on execution rather than constantly confirming details. They create confidence, support flow, and enable teams to operate smoothly under pressure.

Purposeful Visuals: More Than Decoration

When I lead workshops or conduct site visits, I often emphasize that visuals must serve a clear purpose. Too often, organizations create dashboards, boards, or screens that are visually impressive but lack real meaning. They become background noise, ignored by the people who need them most.

At the creperie, the ingredient displays were functional. Each visual cue had a role: ensuring accuracy, supporting flow, and preventing errors. The display wasn’t designed to impress or decorate—it was designed to enable. This is a critical lesson for leaders in any sector: visual management is effective only when it communicates the right information to the right people at the right time.

The Intersection of Function and Art

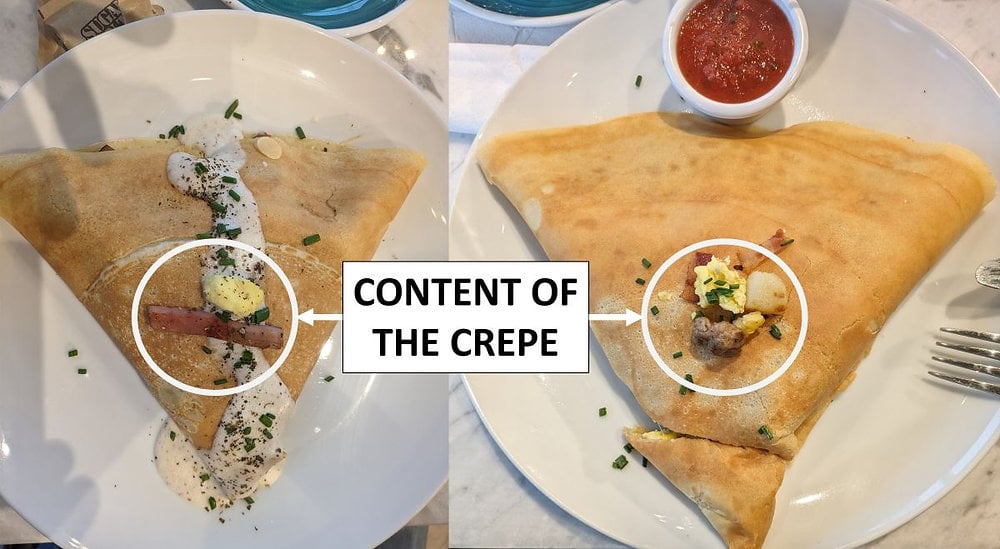

Another striking aspect of the creperie experience was the artistry embedded in the work. Each plate was arranged with care: ham folded precisely, cheese melted evenly, eggs centered, and garnishes placed deliberately. This attention to detail wasn’t superficial—it was integral to the process.

In Lean thinking, we often emphasize respect for people, which manifests in coaching, engagement, and structured problem-solving. But respect can also be expressed in the care and precision of work. When teams take pride in the visual and functional quality of their output, it communicates standards, values, and care. Customers—and staff—notice.

I’ve observed similar attention to visual detail in surgical suites, sterile processing areas, and high-volume manufacturing lines. Visual organization, clarity, and presentation are functional, but they also signal discipline, teamwork, and commitment. The visual layout communicates not only what to do but also what the team values.

Preventing Problems Through Design

Lean principles encourage designing systems that prevent errors before they occur. Mistake-proofing, or poka-yoke, is often associated with mechanical or process controls. At the creperie, the same principle was applied through a simple visual display.

By arranging ingredients visibly and logically, the creperie minimized the chance of errors. Staff no longer had to rely solely on memory or verbal communication. Visual cues provided instant confirmation, preventing mistakes in real time.

This proactive approach is a powerful lesson for healthcare and manufacturing: systems that prevent errors are more effective than those that rely on detection after the fact. Thoughtful visual design is a key element of error-proofing, enhancing both quality and confidence.

Visual Management Supports Flow

One of the often-overlooked benefits of clear visuals is the way they support flow. When information is visible and intuitive, staff can work without unnecessary stops or clarifications. Orders move smoothly, tasks are completed efficiently, and the pace of operations is maintained.

In the creperie, this meant customers received their dishes correctly and promptly. In a hospital or factory, it translates to fewer bottlenecks, faster cycle times, and reduced risk of errors. Flow is not just about speed—it’s about enabling people to focus on the right work at the right time. Visual management is one of the simplest and most powerful ways to sustain that flow.

Observation and Feedback

Another practical benefit of well-designed visuals is the opportunity for observation and feedback. When expectations are clear, deviations are easier to spot and correct. Leaders can provide targeted coaching, reinforce standards, and guide continuous improvement.

At the creperie, visual organization allowed servers to self-check their work. Mistakes were less likely to happen, but if they did, the team could identify and correct them quickly. This same principle applies in healthcare, manufacturing, and service environments: clarity enables accountability and learning.

Lessons in Respect and Engagement

Lean is fundamentally about respect for people. Visual management contributes to that respect by making work easier, safer, and more predictable. The creperie illustrated this principle beautifully. By designing a system that empowered staff, reduced errors, and supported consistent quality, the team demonstrated respect for both employees and customers.

Attention to detail and thoughtful design signal that the work matters. Customers experience quality, staff experience clarity, and the organization benefits from smoother operations. Small gestures, like arranging ingredients thoughtfully, communicate a culture of care and pride.

Seeing Lean Everywhere

Perhaps the most important lesson from breakfast is that operational excellence is not confined to factories or hospitals. Lean thinking is a lens—a way of seeing and analyzing work. It is about noticing inefficiencies, designing clarity into processes, and respecting people through thoughtful system design.

The creperie had no posters about Lean. No laminated standard work documents. Yet it was a live demonstration of core Lean principles: flow, visual management, error prevention, and respect for people. It was simple, quiet, and elegant—qualities often overlooked in formal operational improvement programs but no less powerful.

As leaders and improvement practitioners, we can learn from these moments by observing the world around us. Lean lessons exist in unexpected places: a patient care process, a production line, or a small breakfast restaurant. Observing, reflecting, and asking why something works can inspire changes that have broader impact.

Practical Takeaways

From this experience, a few lessons resonate across industries:

- Clarity Prevents Confusion: Visual cues reduce cognitive load, allowing staff to focus on execution rather than decision-making in the moment.

- Visuals Must Be Simple and Timely: Overcomplicated or hidden visuals create barriers rather than support. Simple, visible, and actionable visuals are most effective.

- Attention to Detail Communicates Values: Thoughtful presentation—whether of food, parts, or a workflow—reflects pride in work and respect for those served.

- Design Systems for Users: Visual management and process design should make work easier and safer for those performing it.

- Quiet Excellence is Powerful: Effective systems don’t need to be flashy or formalized. Small, thoughtful designs often create disproportionate improvements in quality and flow.

These lessons are applicable in manufacturing, healthcare, service industries, and beyond. They remind us that operational excellence is not always about large initiatives or high-tech solutions. It’s often about careful design, simple controls, and attention to the details that make work smoother, safer, and more effective.

Closing Thoughts

Operational insight often comes in unexpected moments. A simple breakfast can become a powerful lesson in Lean thinking. Visual management is not just about boards and dashboards—it is about clarity, error prevention, alignment, and respect.

Whether managing a hospital unit, a factory floor, or a small restaurant, the principles remain the same. Observing carefully, designing thoughtfully, and acting intentionally can transform ordinary work into a system of excellence.

Sometimes, the most profound lessons in operational improvement come not from a workshop or a meeting but from a quiet morning with a well-made crepe.

Comments