Why Confusing Problems and Opportunities Weakens Operational Excellence

In 2004, not long after I started a new role at a Minnesota manufacturing company, I experienced a moment that has stayed with me ever since. During an operations meeting, I raised what I believed was a clear production problem—something concrete that needed attention. Before I even finished my sentence, someone jumped in and said, “Didier, we have no problems here. We only have opportunities.” I paused, wondering if this was the famous “Minnesota nice” culture at work or something else entirely. After a moment of reflection, I answered honestly: “Well, this is definitely not an opportunity. This one is a problem.”

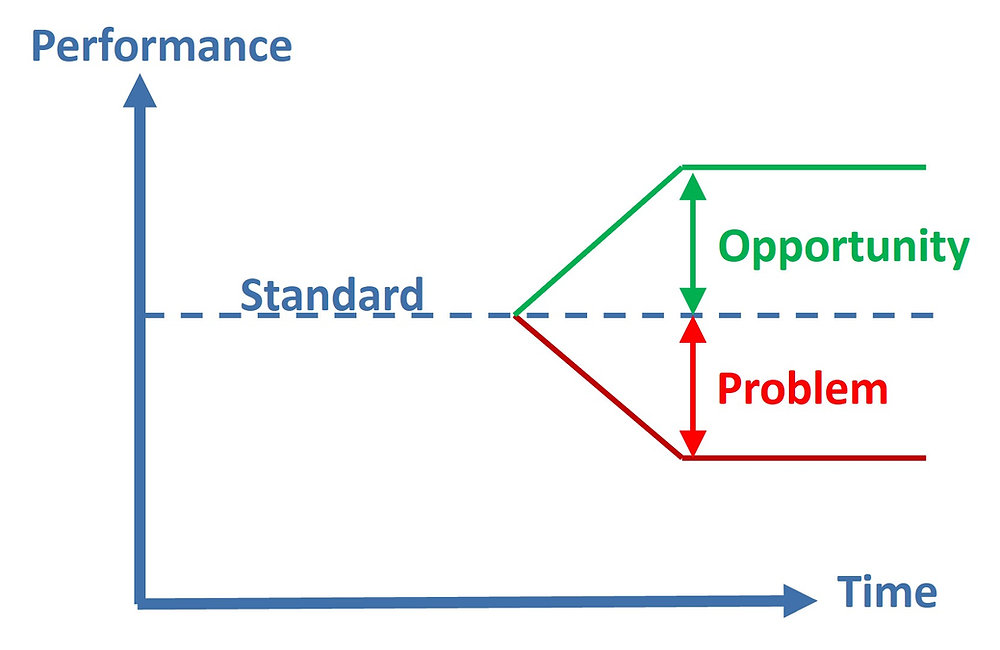

That simple exchange revealed something deeper about operational maturity. Many organizations develop an aversion to using the word “problem,” as though calling something a problem is negative, discouraging, or critical of the people involved. But avoiding the reality of a problem does not make operations stronger. In fact, it weakens the organization’s ability to learn, solve, and improve. When a standard degrades, that is not an opportunity. It is a problem. And if we can’t name it accurately, we cannot solve it effectively.

Across manufacturing, healthcare, and service industries, I have seen how language shapes behavior. The way leaders talk about problems influences how people respond to abnormalities, how quickly issues surface, and how effectively teams improve. A healthy operational culture does not hide from problems. It surfaces them immediately, treats them as gifts, and responds with scientific thinking. But that process only works when everyone understands the difference between a problem and an opportunity.

This distinction is not semantic. It is foundational to Lean thinking, continuous improvement, and the capability development of every team member. Confusing the two creates wasted effort, misdirected energy, and slow improvement cycles. Getting the distinction right strengthens problem-solving capability, clarifies expectations, and accelerates progress.

This post explores why the difference between problems and opportunities matters, how to recognize each clearly, and how leaders can reinforce the right behaviors to build a culture of operational excellence.

Why Language Matters in Lean Organizations

In Lean systems, clarity is power. Clarity about standards, clarity about expectations, clarity about process conditions, and clarity about abnormalities. When teams lack that clarity, they spend more time interpreting situations, debating definitions, or aligning understandings than actually fixing what is wrong. Leaders often underestimate how deeply their language sets the tone.

Organizations that avoid the word “problem” tend to develop several predictable issues:

- People hesitate to raise concerns

- Problems are discovered late

- Data becomes distorted to avoid uncomfortable conversations

- Leaders conclude that operations are “stable” when they are not

- Improvement efforts focus on symptoms rather than causes

- Teams drift toward workarounds instead of root cause analysis

In contrast, organizations that treat problems as normal—inevitable, expected, and welcome—develop stronger muscles for surfacing issues, understanding actual conditions, and applying PDCA thinking. The daily work becomes safer, more predictable, and more aligned.

The word “problem” in Lean is not negative. It is simply an abnormality from a standard. That standard could be related to safety, quality, delivery, cost, workflow, staffing, inventory, documentation, information flow, or any other element of operational performance. Whenever the actual condition differs from the expected condition, that gap is a problem.

Avoiding the word does not make the situation less real. It only delays the learning.

A Problem Is a Deviation From the Standard

The simplest and most accurate definition of a problem is this: a problem is a deviation from the standard.

If the work is supposed to be done a certain way and it is not done that way, that is a problem. If the equipment is supposed to perform at a certain capability and it does not, that is a problem. If a process is supposed to take a predictable amount of time and suddenly takes twice as long, that is a problem.

When organizations adopt this definition, everything becomes clearer:

- Problems can be surfaced quickly

- Leaders and teams share the same language

- People feel safer raising concerns

- Standards become more meaningful

- Waste is exposed and addressed regularly

One of the best-known examples comes from outside manufacturing. During the Apollo 13 mission, astronaut Jim Lovell radioed to NASA, “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” He did not describe it as an opportunity. No one would. The situation was an abnormality of the highest order, and the mission’s survival depended on identifying the exact nature of the problem and correcting it.

In daily operations—whether in a factory, a hospital, or a service center—problems may not be as dramatic, but the principle is the same. You fix a problem by restoring the standard. You do not improve the standard until you have stabilized it.

Problem-Solving Starts With Locating the Problem

Every problem has a root cause, but the first task is not jumping to the root cause. The first task is accurately identifying the problem itself.

In my experience, teams often skip this step. They rush into brainstorming causes, testing solutions, or debating opinions before they even align on where and when the problem occurred. Strong Lean organizations do the opposite. They slow down upfront so they can move faster later.

The sequence is simple but powerful:

- Clarify the problem: What exactly is wrong?

- Identify the location: Where did it occur?

- Understand timing: When did the deviation begin?

- Compare actual vs. expected condition

- Gather facts at the source (gemba)

- Only then, begin to explore root cause

If the team cannot define the problem precisely, the root cause investigation will be a guessing exercise. The eventual countermeasures will not address the true underlying issue. Firefighting will continue. The problem will resurface. People will lose confidence in the process.

Accurate problem definition is the gateway to effective improvement.

Root Cause Analysis Belongs to Problems, Not Opportunities

Another way to distinguish problems from opportunities is to examine whether a root cause exists.

A problem has a root cause because it is linked to a deviation from a standard. Something drifted. Something failed. Something changed. Something was not followed. Something did not perform as expected.

When a problem exists, the team’s goal is to identify the factor that produced the deviation and develop countermeasures that either eliminate that factor or reduce its influence. This is structured, hypothesis-driven work. It requires discipline in observation, documentation, and experimentation.

An opportunity is not rooted in failure. It is not a deviation. It is an aspiration. An opportunity is about going beyond the current standard, not returning to it. Because there is no failure involved, there is also no root cause to investigate.

Opportunities require different thinking:

- They involve ideation and creativity

- They explore future possibilities rather than current conditions

- They challenge existing assumptions

- They require setting a new standard, not restoring an old one

Confusing the two leads to wasted time. When teams try to apply root cause analysis to opportunities, they end up forcing the wrong method onto the wrong situation. The conversation becomes muddled. Energy gets drained. Progress slows.

When they treat problems like opportunities, issues go unresolved, gaps persist, and teams become discouraged.

Both are important. But they are not interchangeable.

Opportunities Are About Elevating the Standard

An opportunity involves identifying ways to elevate performance, design a better future state, or challenge existing processes. Examples include:

- Reducing cycle time beyond the current expectation

- Improving first-pass yield after stabilizing the existing standard

- Streamlining the onboarding process for new employees

- Redesigning a production cell to improve flow

- Using automation after stabilizing manual processes

- Lowering inventory levels through improved synchronization

In these cases, the current condition is not wrong—it can simply be better.

Teams are free to explore ideas, test concepts, and design improvements that deliver more value. This work is open-ended, creative, and forward-looking. It is essential for long-term competitiveness. But it does not replace problem-solving. It builds on the foundation that problem-solving creates.

The healthiest organizations can do both. They restore standards quickly and reliably when problems occur, and they raise standards continuously through opportunities for improvement. But they never mix the two.

Why the Distinction Matters to Lean Management Systems

Strong Lean management systems depend heavily on clarity about standards and problems. Daily management routines, visual controls, leader standard work, and problem escalation processes all rely on identifying deviations quickly and accurately. When teams hesitate to call something a problem, the entire management system weakens.

Here are some examples of what happens when problems are mislabeled as opportunities:

- Daily huddles fail to surface abnormalities

- Leaders lose visibility into operational risks

- Teams normalize degraded performance

- Improvement prioritization becomes unclear

- Chronic issues get absorbed into the background noise

- New employees learn the wrong behaviors

In contrast, when an organization makes the distinction explicit and consistent, the management system strengthens. Problems surface quickly. Leaders respond appropriately. Teams build problem-solving capability. Opportunities for improvement become more strategic. The entire continuous improvement engine becomes more aligned and effective.

What Leaders Can Do to Reinforce the Right Behaviors

If organizations want to build a culture that distinguishes clearly between problems and opportunities, leaders play a central role. Their language, reactions, and expectations shape how teams respond.

Here are practices that reinforce clarity:

- Define the standard visibly and simply

- Teach teams that problems are deviations, not personal failures

- Create psychological safety for surfacing abnormalities

- Praise early detection, not firefighting

- Apply PDCA rigorously to problems

- Use different methods for opportunity-based improvement

- Avoid turning opportunities into forced problem statements

- Model the behavior: call problems “problems”

Leaders also benefit from developing a habit of asking three simple questions whenever someone brings an issue forward:

- What is the standard?

- What is the actual condition?

- Is this a problem or an opportunity?

Those three questions create instant alignment. They prevent confusion. They clarify the right path forward.

Final Thoughts

The moment in that 2004 meeting taught me something essential about operational cultures: an organization’s relationship to the word “problem” reveals its relationship to learning. If problems are avoided, softened, or reframed into something more comfortable, teams will hesitate to surface issues. Root causes will remain hidden. Standards will drift. Improvement will plateau.

But when problems are treated as normal, expected, and valued, the entire organization gains strength. Learning accelerates. Confidence increases. Teams become more capable. Processes stabilize. Improvements take root. And the culture shifts toward continuous improvement.

Problems require restoring the standard. Opportunities require elevating the standard. Both are important. But they require different mindsets, different methods, and different leadership behaviors.

Naming things clearly is the first step. Solving them effectively is the next.

If your organization is struggling to distinguish between problems and opportunities—or to build a culture that welcomes both—I’d be glad to help you strengthen your management system and develop the capability of your teams.

Comments