Turning Personal Chaos into a Pull System: How Type C Kanban Transformed My Leadership Work

Twenty years ago, I was serving as a value stream manager in a large manufacturing organization. My role was to lead a significant Lean transformation that spanned production lines, support functions, and cross-functional teams. At the time, I was deeply immersed in applying Lean principles to stabilize processes, improve flow, and eliminate waste on the shop floor. Like many leaders who adopt Lean for operations, I eventually began applying the same thinking to my own work.

Leader Standard Work was my first major shift. It helped me organize routines, establish cadence, and ensure that essential leadership behaviors happened with intention rather than good intentions. I built a structure for daily Gemba walks, coaching conversations, review of key performance indicators, and small problem-solving cycles that kept me close to the work and close to my people. The system worked. It brought discipline and clarity to my role.

But after several cycles of reflection, improvement, and real-world experimentation, I ran into a surprising limitation. Leader Standard Work was necessary, but it was not sufficient.

The Lean transformation I was leading demanded a significant load of work that did not fit neatly into a repeating cycle. These were projects, follow-up actions, decisions requiring deeper thinking, stakeholder engagements, and unexpected issues that arose from the very transformation we were driving. They were all important, but none of them were cyclical. I could not place them into a weekly or daily leader standard work routine without overwhelming the system or compromising the integrity of the routines themselves.

These non-cyclical tasks repeatedly collided with the cyclical ones. The result was instability in my work. Some days, I found myself pulled in directions I had not planned for. Other days, I struggled with too many active tasks competing for attention. The tension between cyclical and non-cyclical work became a real operational problem. And like any operational problem, it needed a system.

That realization led me to revisit something I had learned years earlier on the shop floor: Type C Kanban.

Exploring the Idea of Type C Kanban for Leadership Work

In manufacturing, Type C Kanban is a hybrid system combining elements of both Type A (fill up) Kanban and Type B (sequential) Kanban. It is particularly powerful when you need both structure and flexibility. It provides limits that prevent overload while enabling controlled flow based on actual need. The more I thought about it, the more I realized the analogy was compelling.

Why not apply Type C Kanban to leadership work?

The more I reflected, the clearer it became that my non-cyclical tasks behaved very much like a mixed environment flow. They varied in scope, urgency, and complexity. They often arrived unpredictably. They needed a way to enter and progress through a workflow without overwhelming capacity. And most importantly, they needed visual control.

This insight led me to create a personal pull system for leadership tasks—a Type C Kanban for myself.

Designing the First Version of the System

The first version was simple. I capped the number of “active” tasks at three. This was my work-in-process (WIP) limit. Only three non-cyclical tasks could be worked on at any given time. Everything else went into a queue. I wrote each task on a Post-it note and placed it on a small personal board. When one task was completed, a square Kanban authorized the next task to be pulled.

The brilliance of the system was its simplicity. I no longer started five, ten, or twelve tasks at once. I no longer had to remember what was pending or worry about what I was forgetting. Everything was written down, visible, sequenced, and under control. And because the system defined the limits, the feeling of being overloaded diminished dramatically. I had created a mechanism that maintained both flow and focus.

But there was one more step required. For the system to integrate effectively with my leadership routines, it needed time in the day.

Integrating Personal Kanban into Leader Standard Work

To ensure the system was not an afterthought, I added two routines to my Leader Standard Work:

- Review personal Kanban at the start of the day

- Advance personal Kanban during designated blocks of focused time

These two routines were small but transformative. Reviewing the Kanban each morning ensured a deliberate start to the day. It prevented firefighting, emotional reactions, and unplanned pivots. Advancing the Kanban ensured that non-cyclical work made steady progress rather than stalling for weeks at a time. Slowly, the non-cyclical tasks became cyclical because the routines were now part of the system.

The impact was immediate and profound. The integration stabilized my work. Tasks that used to get stuck moved smoothly. My attention was no longer scattered. My leadership work—once full of interruptions and context switching—developed rhythm and predictability.

Over time, the system improved.

Evolving the System Through Lean Thinking

Like any Lean system, my personal kanban evolved through reflection and experience. As the complexity of my role grew, I realized that not all tasks had equal importance. Some tasks had high urgency but low long-term value. Others were strategically critical but not urgent. This led me to incorporate elements from the Eisenhower priority matrix to categorize work by urgency and importance. That refinement helped me make clearer decisions about what should enter the Kanban and what should not.

Later, I incorporated ideas from Jim Benson, whose work on personal kanban gave language and structure to concepts I had been experimenting with. The combination of Lean principles, visual management, capacity limits, and reflection routines created a powerful system that not only improved my productivity but also strengthened my leadership.

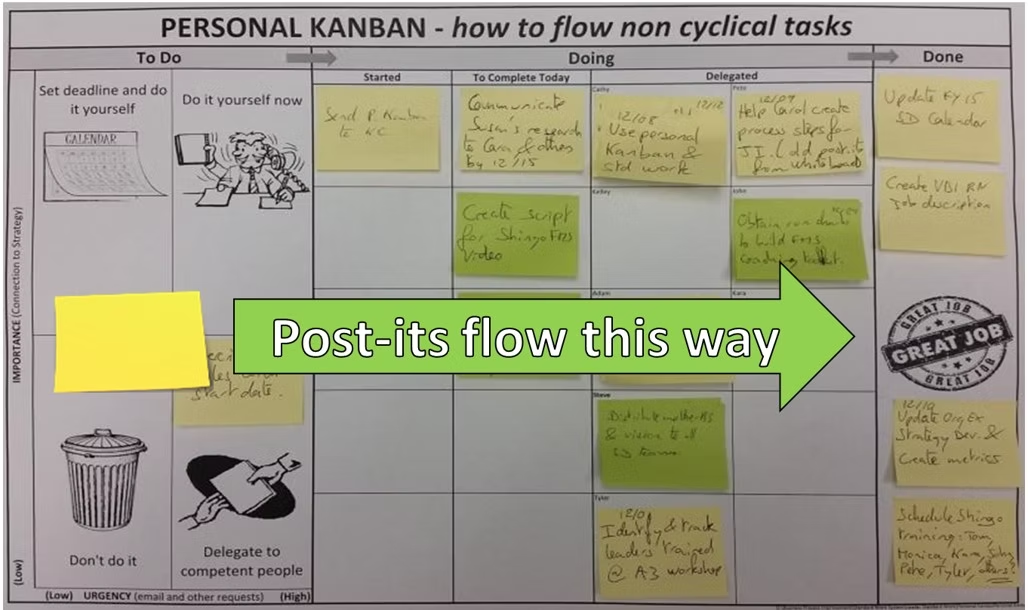

The photo I often share shows where the system eventually landed. It represents years of learning and refining a structure that started with a simple idea: leaders need a pull system just as much as the shop floor does.

Why Leaders Need a Personal Pull System

Most leaders operate in a mixed environment of cycles, interruptions, projects, decision-making, coaching, crisis response, and long-term work. It is an environment prone to overload. And overload undermines leadership effectiveness.

Without a personal pull system, leaders experience:

- Constant task switching

- Unpredictable days

- Invisible work accumulating

- Reactivity instead of intentionality

- Repeated cycles of catching up

- Diminished ability to coach others

A leader who cannot stabilize their own work cannot stabilize the work of others. An overloaded leader cannot support problem-solving, see the system clearly, or make decisions aligned with long-term priorities.

A pull system for leadership work addresses these challenges by:

- Creating visibility

- Setting limits

- Establishing flow

- Avoiding overburden

- Building discipline

- Supporting reflection

- Improving problem recognition

What started as a pragmatic solution for myself has become something I now routinely teach leaders. Whether in healthcare, manufacturing, or service organizations, leaders benefit from a mechanism that manages the unpredictable and protects their ability to lead.

How a Pull System Elevates Leadership Behaviors

A common misconception is that personal productivity systems exist simply to get more done. But in a Lean context, the purpose is much deeper. A personal pull system strengthens leadership behaviors and contributes to a healthier organizational culture.

- It reinforces intentionality.

- It helps leaders be present during coaching and Gemba walks.

- It reduces emotional reactivity.

- It supports better prioritization.

- It models structured problem solving.

- It encourages reflection.

When leaders stabilize their own work, they set the tone for the organization. Their behaviors send a signal about how work should be approached, how problems should be surfaced, and how learning should occur.

The Connection to Lean Thinking

At its core, applying Type C Kanban to leadership work is a natural extension of Lean thinking. Lean has always emphasized:

- Flow

- Pull

- Visual management

- Problem visibility

- Respect for people

- Learning cycles

- Continuous improvement

Leaders frequently apply these principles to operations but overlook their relevance to their own workload. When leaders adopt a pull system, they apply Lean to themselves. They create stability, reduce wasteful switching, and improve their ability to understand the system.

In many ways, this is the essence of Lean leadership—modeling what we expect others to practice.

Reflections After Twenty Years

When I look back on that period as a value stream manager, I realize that the biggest improvements I made were not on the shop floor but in how I organized my work. The combination of leader standard work and personal kanban gave me a stable system that supported high performance without burning out. The habits I developed then still ground my leadership practice today.

Leaders operate in an environment full of competing demands. It is easy to get pulled into a cycle of urgency that prevents thoughtful, strategic action. The pull system I built allowed me to escape that trap. It provided clarity, boundaries, and a structure for continuous learning.

And like all good Lean systems, it continues to evolve.

Closing Thoughts for Leaders

Every leader I meet faces the same challenge I once faced: too much work, too many priorities, and too little time. The answer is not to work faster or push harder. The answer is to design a system for your work.

A personal pull system grounded in Lean principles gives leaders the structure to navigate complexity, maintain focus on what matters most, and support the organization with stability and intention.

Leaders deserve systems, not chaos. And when leaders live inside a pull system, they create the conditions for everyone else to do the same.

Comments